**Another Proof That Leonardo da Vinci Was a Genius**

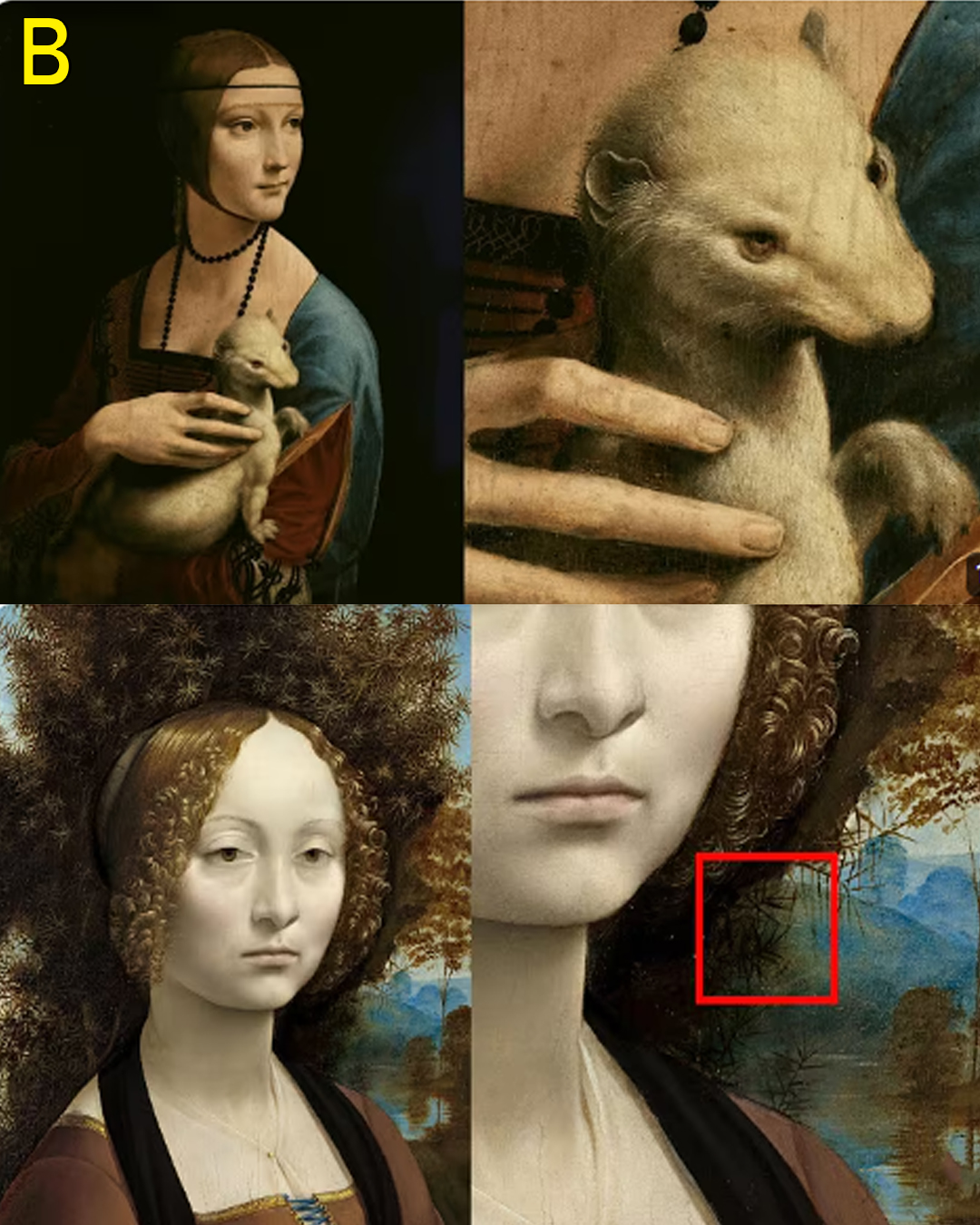

Leonardo da Vinci’s “Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci,” painted in the late 15th century, stands as the earliest known female portrait by the Renaissance master—and the only Leonardo painting in the United States.

Traditionally, the sitter is identified as Ginevra de’ Benci, a young Florentine noblewoman celebrated for her beauty and virtue. But this artwork is far more than a conventional portrait, holding mysteries that continue to intrigue art historians centuries later.

Ginevra was born into a prominent Florentine family, living near the iconic Ponte Vecchio. At the time of the portrait, she was about sixteen years old, admired for her looks and character, and the subject of poems and sonnets.

Leonardo, then just twenty-one and still working in Verrocchio’s workshop, received the commission around 1474, a pivotal moment as he shaped his artistic identity.

Leonardo’s approach was groundbreaking. Rather than the rigid profile portraits typical of Italian tradition, he painted Ginevra almost facing the viewer, with a subtle turn of the shoulders.

This pose, inspired by Northern European conventions, allowed for a more intimate and psychological reading of the sitter. Ginevra’s pale skin glows in natural light, her expression introspective and enigmatic, making her seem like a real, relatable person.

The background is equally innovative. Ginevra is set before a landscape with water and trees, creating a sense of infinite space. Leonardo used aerial perspective—colors cooling and fading into the distance—to convey depth, a technique he would perfect throughout his career.

Behind her, a dense backdrop of juniper (ginepro in Italian) not only provides visual contrast but also symbolizes female virtue and purity. The juniper is a clever play on Ginevra’s name, linking her identity to ideals of chastity and moral integrity.

One of the most astonishing discoveries is the presence of Leonardo’s own fingerprints on the painting, preserved among the branches of the juniper. These marks show how he used his fingers to blend paint and soften transitions, an early sign of his revolutionary “sfumato” technique—soft contours and forms that dissolve gradually, rather than sharp lines. This tactile evidence offers a glimpse into Leonardo’s creative process and genius.

But the greatest mystery lies on the back of the painting. There, a symbolic emblem features a juniper branch flanked by laurel and palm, with a Latin inscription: “Virtutem forma decorat”—“Beauty adorns virtue.”

The laurel, associated with poets and intellect, and the palm, a symbol of victory and moral strength, suggest a deeper meaning. Recent research points to Bernardo Bembo, a Venetian diplomat and platonic admirer of Ginevra, as the likely patron. Bembo’s personal emblem included both laurel and palm, and beneath the current inscription, infrared analysis revealed Bembo’s original motto, “Honor and Virtue.”

Bembo commissioned poems praising Ginevra, and their relationship reflected the Renaissance ideal of platonic admiration—intellectual and emotional bonds celebrated in public rather than romantic secrecy.

This dual symbolism on the reverse of the painting suggests that the portrait was not simply a marriage commemoration, but a tribute to Ginevra’s virtue, intellect, and the admiration she inspired.

While the exact details remain uncertain—was the painting commissioned for her marriage, or as a gesture of admiration from Bembo?—the portrait’s two sides may represent different intentions, or even multiple patrons.

This ambiguity, along with Leonardo’s technical brilliance and psychological insight, makes “Ginevra de’ Benci” a masterpiece that continues to spark debate and wonder.

Leonardo’s genius is evident not only in the lifelike portrayal and innovative techniques, but in the layers of meaning and mystery embedded in the work. The painting invites viewers to look deeper, to question, and to appreciate the complexity of Renaissance art and the mind that created it.