This Was Not Supposed to Survive”: The Ethiopian Bible That Reveals Forbidden Texts Hidden for Centuries

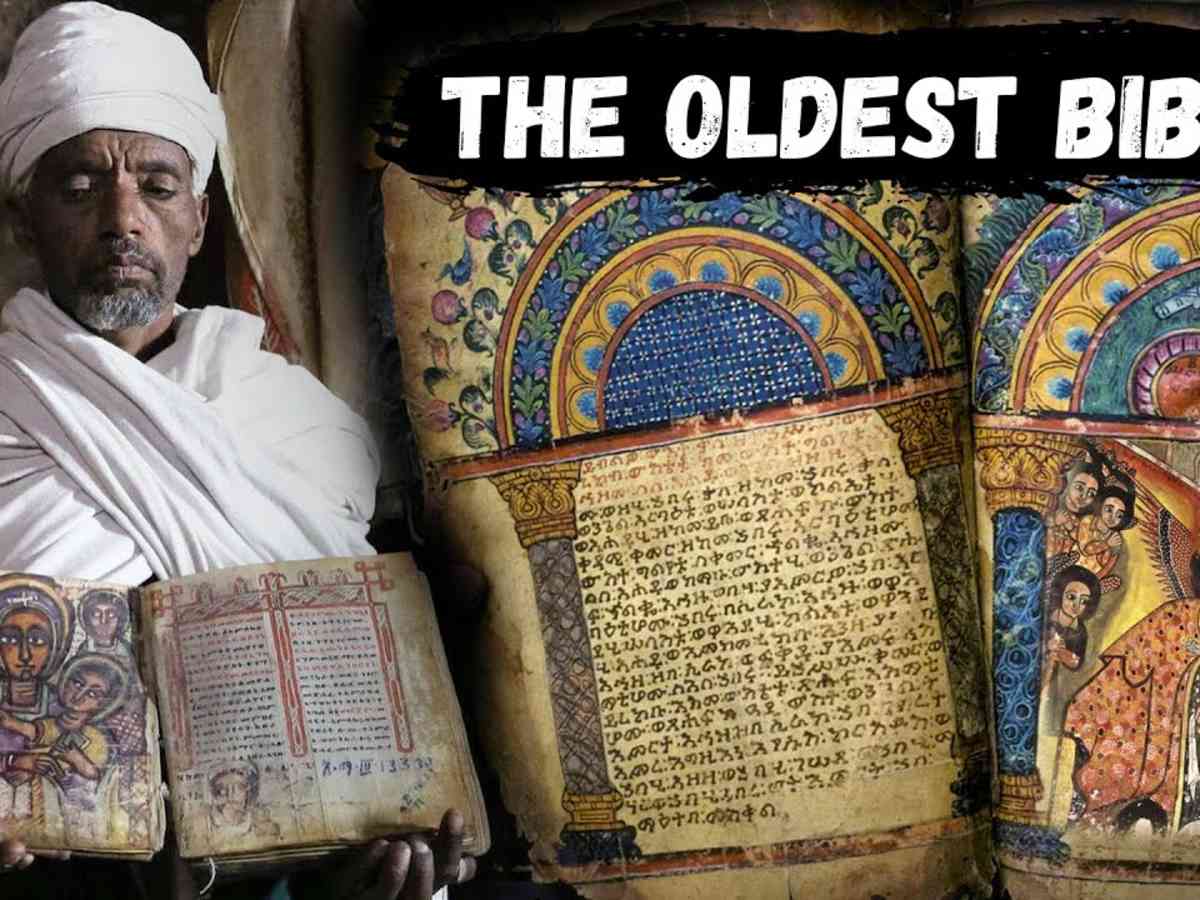

For centuries, the story of the Bible has been one of finality—a closed canon, shaped by councils and consensus, its contents sealed by tradition. But Ethiopia’s Christian tradition stands apart, older than most European churches, independent from Rome and Constantinople, and quietly safeguarding a different scriptural legacy.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church preserved its sacred texts in Ge’ez, a language few outsiders can read. When scientists and historians were granted rare access to these ancient manuscripts, they expected familiar scriptures. Instead, they found themselves in an alternate Christian reality, one that included books and passages deliberately excluded from Western Bibles.

The Ethiopian Bible was not a simple translation but a compilation of forbidden texts—apocryphal, heretical, or deemed too dangerous to canonize. Among them were expanded versions of the Book of Enoch, which describe angels descending to Earth, imparting forbidden knowledge, and producing hybrid offspring that even God feared. These accounts are not vague allegories but detailed, confident testimonies, unsettling scholars with their matter-of-fact tone.

What disturbed researchers most was the Bible’s emphasis on knowledge—who possessed it, who lost it, and the consequences of sharing it. While Western scriptures focus on salvation and redemption, the Ethiopian Bible explores cosmic hierarchies and a universe governed by strict, merciless order. Humanity is depicted not as the pinnacle of creation, but as a volatile experiment, capable of greatness and disaster.

One passage, particularly chilling, describes a post-Flood moment where certain truths were erased from human memory—not out of mercy, but out of fear. The text warns that if humans remembered what they once knew, they might reclaim powers never meant for them. The language is precise and modern, challenging centuries of theology that centers God’s relationship with humanity on love. Here, love exists, but so does containment and control.

The discovery’s aftermath was marked by hesitation. Conferences were postponed, academic papers stalled, and researchers became cautious, stressing the need for careful interpretation. The excitement faded into a coordinated restraint, as if the implications were too profound to articulate openly.

For Ethiopian clergy, these texts were no revelation. They were inherited truths, preserved because they were misunderstood elsewhere. In private, some suggested that the exclusion of certain books from the Bible was as much political as spiritual, shaped by leaders who feared chaos more than ignorance. The realization unsettled many: the Bible’s canon was not just a divine selection, but a historical curation, shaped by fear and control.

For believers raised on the idea of a complete, divinely curated Bible, the existence of such texts feels like a betrayal—not by God, but by history. What else was removed? What questions were never asked? What kind of faith might have emerged if these passages had survived in the collective consciousness?

The Ethiopian Bible offers no comforting answers. It presents a world where divine beings argue, fail, and impose limits because humanity is dangerously capable. As news of the discovery spread, reactions ranged from awe to defensiveness. Some dismissed the texts as fringe mythology, others saw them as proof that institutional religion has always curated truth.

Yet the sophistication and consistency of the manuscripts, their seamless integration into Ethiopian tradition, defy easy dismissal. This is not a forgery or cult fantasy, but a surviving branch of Christianity deliberately pruned elsewhere.

The silence that followed is telling. Such discoveries do not fade—they linger, challenging certainty and whispering that what we know may only be what we were allowed to keep. The Ethiopian Bible remains: fragile, explosive, and a reminder that history is often written not by the faithful, but by the fearful. Once forbidden words resurface, they ask questions that refuse to go away.

—