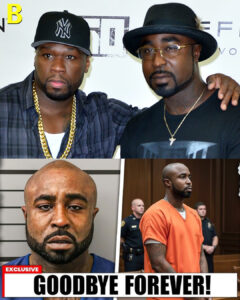

Gerald and Sean Levert, sons of Eddie Levert of The O’Jays, were born into R&B royalty and spent their lives chasing musical greatness and their own place in history.

In the 1980s, the brothers formed LeVert with childhood friend Marc Gordon, finding early success with hits like “Casanova,” which became the first New Jack Swing song to top the R&B charts and went gold. Gerald’s powerful baritone and Shawn’s smooth harmonies set them apart, and soon they were headlining tours, winning awards, and earning respect beyond their father’s legacy.

Gerald’s ambition pushed him to a solo career, and he quickly became one of the last great soul singers, releasing platinum albums and collaborating with legends like Keith Sweat and Johnny Gill in the supergroup LSG. Shawn tried his hand at a solo album but never matched Gerald’s success.

Behind the scenes, the grind was relentless. Gerald supported a large family, maintained two homes, and kept friends and relatives on his payroll. He pushed through pain and exhaustion, touring and recording even when his body begged for rest. By the mid-2000s, the music industry was changing, and Gerald’s soulful style was being crowded out by hip hop.

Still, he kept working, relying on prescription painkillers to get through shows. In November 2006, after returning from a tour in South Africa, Gerald fell ill with pneumonia. He was found dead in his Cleveland home at just 40 years old, with seven prescription bottles on his nightstand. The coroner ruled his death accidental—acute intoxication from prescription drugs and pneumonia.

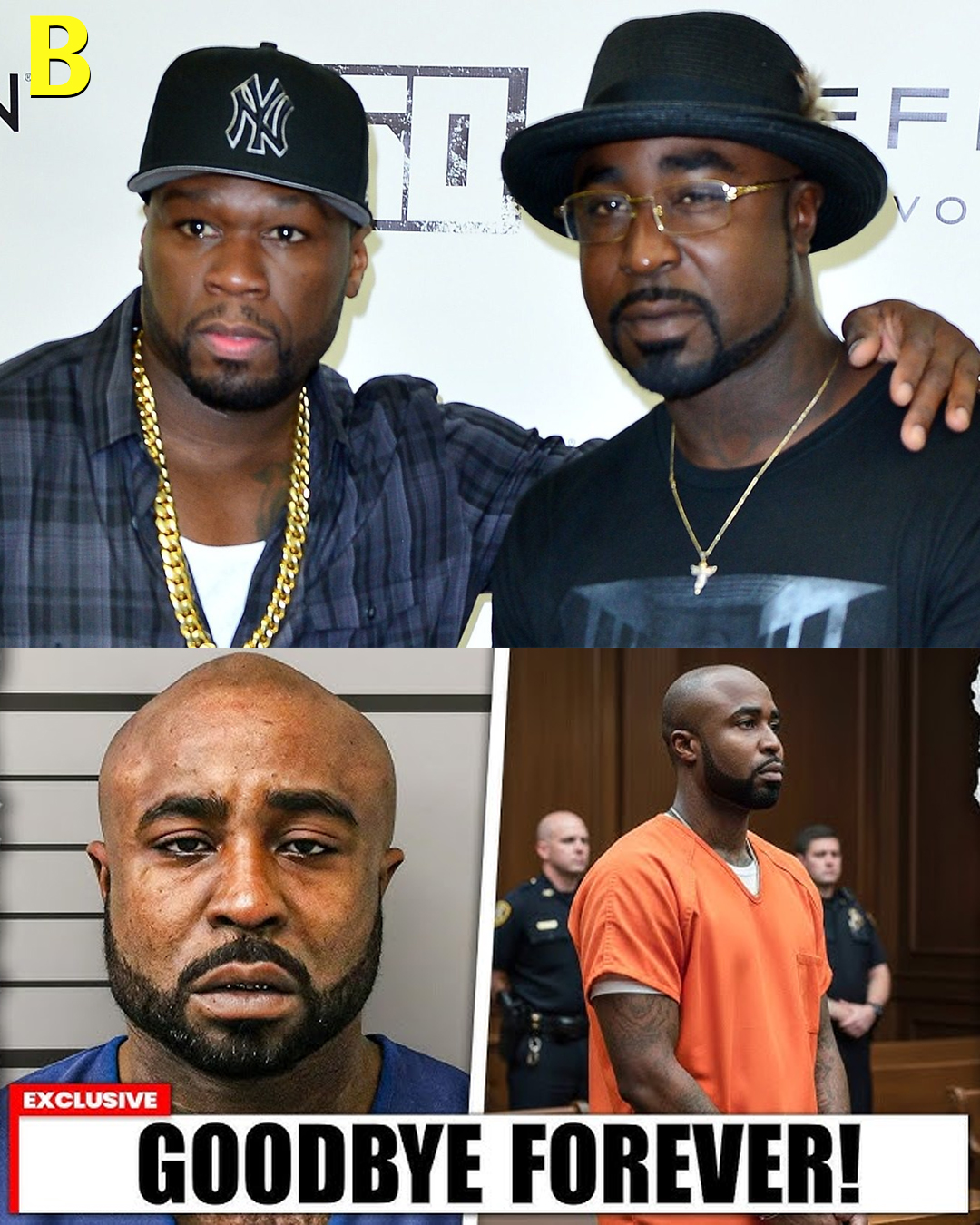

Gerald’s death hit Shawn hard. Already struggling with stalled career prospects and mounting child support debt, Shawn found himself in trouble with the law. In March 2008, Shawn was sentenced to 22 months in the Cuyahoga County Jail for failing to pay $90,000 in child support. He brought his Xanax prescription with him, but jail policy prevented him from taking it.

Six days later, he was hallucinating and in withdrawal, strapped into a restraint chair for 21 hours without medical attention. Shawn died at 39, the coroner citing complications from withdrawal and underlying health issues. His widow sued the county for wrongful death, resulting in a $4 million settlement and the creation of “Shawn’s Law,” mandating medical and mental health screenings for all Ohio county jail inmates.

The Levert family’s grief was compounded by legal battles over Gerald’s estate, which included homes, cars, jewelry, and music royalties. The fight for his legacy stretched on for years, but some victories emerged: Shawn’s Law became policy, saving lives, and Gerald’s music continued to inspire generations of R&B artists.

Eddie Levert, left to mourn both sons, poured his pain into music and memoir, determined to honor their memory. Gerald and Shawn weren’t simply casualties of fame—they were victims of a system that valued profit and performance over health and humanity. Their deaths were preventable, their legacies bittersweet.

The music they made still plays, but the tragedy of their loss reminds us of the cost of ambition and the failures of the systems meant to protect us. Their story is one of talent, heartbreak, and the hope that their music and Shawn’s law will help others live longer, fuller lives.